It’s hardly a state secret that the Austrians weren’t very nice during WWII. Yes, there was a resistance movement, there’s always a resistance movement. But we all know what happened. The Nazis robbed and murdered millions of people. After the war, Austria quietly integrated stolen art into its museum collections and returned to their genteel formality.

“An unfortunate episode, best not talked about, there was nothing to be done,” is my personal take on how Austria, as a nation, grapples with the horror of WWII.

All this is at the front of my mind because I went to see Woman in Gold. The movie tells the story of how Maria Altmann — who fled Vienna in the early days of Nazi occupation – reclaimed Gustav Klimt’s portrait of her aunt. The painting, once housed in the Belvedere Museum – I saw it there years ago – is now in the Neue Gallerie in New York City. Efforts to recover the painting started about the time I started spending a lot of time in Austria; I remember reading reports in the newspapers about the case.

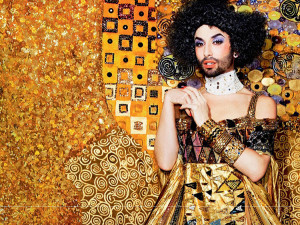

Just a few weeks back, Austria’s new pop culture icon, Conchita Wurst, was recast as Adele Bauer-Bloch, dressed up in golden Klimt style and photographed for a poster promoting the Life Ball, a Europe’s largest AIDS fundraiser. The Ball is in Vienna this year (May 2015). In case you’re not tapped in to European drag artist Eurovision winner culture, well, that’s who Conchita is; she won the Eurovision song contest.

Conchita hails from just up the road from my Austrian home. Literally, it’s only 20 kilometers from where I live when I’m there to Bad Mitterndorf, Conchita’s hometown. Austrians seem to have embraced Conchita whole-heartedly; I regularly drove past a mechanic shop with a banner out front that read, “Welcome to Bad Mitterndorf, Home to Tom Neuwirth, Eurovision Song Contest Winner 2014.” When you know how conservative the region is, you can’t help ponder the weirdness of this. An auto shop celebrating a drag queen in a rural Austrian town. What?

My Austrian husband told me he’d read the powers that decide what happens with the Woman in Gold painting are less than delighted with the latest depiction of Adele Bauer-Bloch as a bearded, cross-dressing pop star. My sense is that Austria is rather amused by it, but to my mind, it’s also another incidence of convenient national amnesia. There’s a scene in Woman in Gold, the movie, where a man confronts Maria Altmann (played by Helen Mirren) saying, “It’s always about the Holocaust with you people, isn’t it? Can’t you move on?” History is so very inconvenient, plus, there was nothing to be done. It is terribly inconvenient to think about the history of this painting in which Conchita is recast. Can’t you just move on?

Conchita would not have been tolerated under the Nazis; this is hardly a ground-breaking epiphany. “Degenerate” art was not allowed, gays and lesbians were treated no better than Jews. Conchita is a phenomenon that is either distinctly modern, or a weird throwback to the Weimer era , a period in which arts and culture thrived. She could have walked right out of Cabaret, the 1972 musical that takes place just as Nazism is rearing its ugly head in Europe.

Conchita as the Woman in Gold embodies Austria perfectly. She is grounded in the immediate but refers to a glorious past, she glosses over the unfortunate aspects of her roots, and we are in on the joke, ha ha, isn’t it funny that we have a bearded lady as our icon, are we not forward looking, you can hardly consider us intolerant, now, can you?

Only yes, we can. Xenophobia is alive and well in Austria. During my winter stay, the newspapers horrified me. Nearly every day I’d see a spread about Muslims juxtaposed with a spread about the need to remain vigilant and militarize. Sometimes, the stories on Muslim communities were human interest, holidays, or interviews with refugees, but they were invariably paired with stories that used the word “Terrorism.”

The country also maintains a willful ignorance about the past in the most unexpected places. I was once confronted by a tour guide for explaining that actually, we know exactly how this Hebrew gravestone ended up in the outer facing walls of one of Graz’s government buildings. Graz was a hotbed of Nazism; Nazis destroyed the Jewish cemeteries and used the stones as pavement and masonry. “We have no idea why this is here,” the guide had said to her English speaking charges.

“Bullshit,” I said, loud enough for everyone to hear. I’d been walking around the city with my family, my in-laws. “We know EXACTLY why it’s here.” And I proceeded to explain what I’ve just told you – it was there because the Nazis put it there. The guide was very angry and accused me of operating a tour without a license, a much greater crime in Austria than being ignorant of history.

I read several reviews characterizing the bureaucrats in Woman in Gold as cartoonish, practically heel clicking Nazis. I’m typically loath to make generalizations, but I’ve been through immigration in Austria and the Austrian government literally affects my daily life. To say those involved are rigid would be an understatement. I thought the bureaucrats accurately portrayed, and I thought that the young journalist who took forever to share his motivation for supporting Maria Altmann’s case showed the hesitancy and optimism of an under-appreciated class of Austrians who want justice for a shameful past while still trying to build a better future for their complicated nation.

Projections everywhere, surely. Please forgive me, I can’t help it. I was raised Jewish, married an Austrian, and my path has taken me, over and over, right into the very messy past of the Jews in Austria. I also pay a distracted sort of attention to the plight of Austria’s minorities, because while I may be American, I’m still Jewish and very much a subclass while in Austria.

There are many things I do not understand, but I know this is true: History does not start at a convenient way-point for those living it. It starts at the beginning, and so should we.

Wonderful piece. History is messy, and complicated without any extras, and when one adds in the Holocaust, the ripples are without a countable number.

I was keen to see this film but your perspective has given me an extra reason and an added dimension.